There were some genuine surprises in the first batch of data from the nation’s 2020 headcount released this week by the U.S. Census Bureau.

Officials in some Sun Belt states were bewildered they did not gain more congressional seats from the apportionment numbers used for divvying up congressional seats among the states. Officials in states like Alabama, Minnesota, and Rhode Island were relieved they did not lose seats they had been expecting to forgo, with some eking out a save by the slimmest of margins.

But the 2020 census is far from over. Here’s what to expect over the next several months.

WHAT’S NEXT?

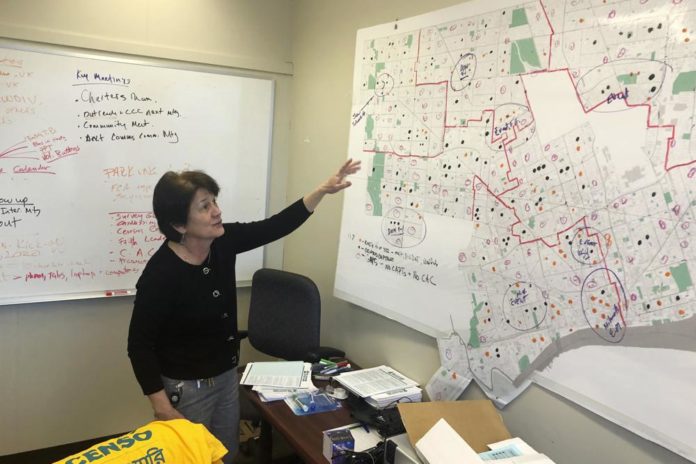

To quote The Carpenters’ 1970s song, “We’ve Only Just Begun.” The 2020 census data released this week — state population counts of every resident — were just the tip of the iceberg of what’s coming later. More detailed data on households’ racial, ethnic, and gender makeup, whether they rent or own their homes, and how everybody is related in their homes, at geographic levels as small as neighborhoods, will be released sometime in August and September. States use this granular data to redraw congressional and legislative districts in a process that often leads to bitter, drawn-out, partisan fights. States are in a tizzy this year since the redistricting data won’t be ready until months past the original March 31 deadline because of the pandemic and the discovery of anomalies the Census Bureau needed to iron out. Twenty-seven states are required to finish redistricting this year. States with tight deadlines this year have gone to court to extend them, changed deadlines through constitutional amendments, and talked about using other data sources. Ohio and Alabama have sued the Census Bureau, trying to force the agency to release the redistricting data sooner.

___

IT WAS MY UNDERSTANDING THERE WOULD BE NO MATH

The biggest task facing the Census Bureau between now and the release of the redistricting data in August and September is implementing a new, controversial statistical technique for protecting the privacy of people who participated in the 2020 census. The method, differential privacy, adds mathematical “noise,” or intentional errors, to the data to obscure any given individual’s identity while still providing statistically valid information. Opponents say it will result in inaccurate data. Supported by at least 16 other states, Alabama’s lawsuit on the redistricting data timeline also challenges the use of differential privacy. Bureau officials say the change is needed to prevent data miners from matching individuals to confidential details that have been rendered anonymous in the massive data release. The Census Bureau is still tweaking the technique, and this week the bureau said its most recent updates meet its criteria for accuracy.

___

ARE THE NUMBERS ACCURATE?

Experts say it’s too early to pass judgment on the accuracy of the apportionment numbers derived from a count challenged by the pandemic, hurricanes, wildfires, and the Trump administration’s failed attempt to add a citizenship question. Three Sun Belt states with large Hispanic populations — Arizona, Florida, and Texas — fell short of earlier estimates, raising concerns among some advocates that Latino communities were missed. Census Bureau officials say they are confident in the accuracy of the apportionment data and that early analyses show the numbers are consistent with what has been seen in the past. Still, because of the difficulties with the count, the Census Bureau has allowed three outside statisticians to review the numbers for their accuracy. The researchers said Thursday that they will issue an initial report in June.

___

CAN A STATE OBJECT?

The Census Bureau allows state, local or tribal governments to request a review of the numbers if they believe the figures are off base. The catch, though, is the Census Bureau won’t make any changes to the figures used for divvying up congressional seats among the states or the redistricting data. Any changes made after a review only would be applied starting in 2022, and that would only be helpful when it comes to getting federal funds. States that are unhappy with the apportionment numbers often sue. New York Gov. Andrew Cuomo hinted at legal action after the apportionment numbers came out this week, showing that 89 more people could have kept New York from losing its congressional seat — if no other states counted any more people. A lawsuit certain to disappear was one brought by Alabama in an effort to exclude from the apportionment numbers of people in the country illegally. Alabama claimed it would lose a congressional seat if undocumented residents were included, but the Cotton State defied expectations by keeping its seventh seat. Former President Donald Trump issued a directive attempting to do the same thing, but President Joe Biden rescinded it when he took office in January.

Republished with the permission of the Associated Press.