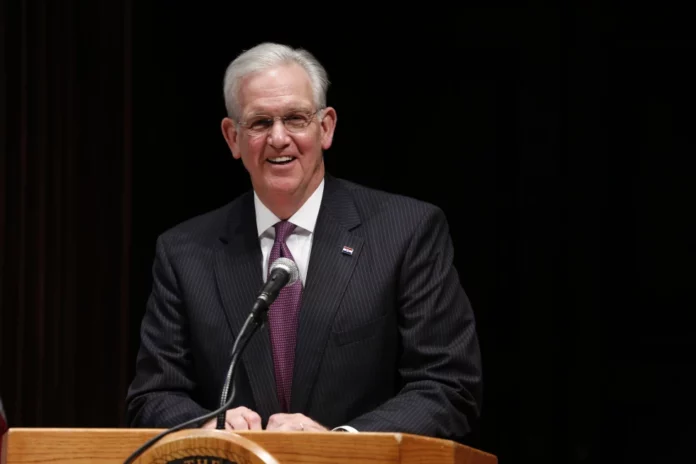

Former Democratic Gov. Jay Nixon of Missouri is joining No Labels‘ increasingly contentious effort to lay the groundwork for a moderate third-party presidential ticket in the 2024 election. He gives the embattled organization another prominent ally amid escalating concerns from Democratic officials that the No Labels campaign could unintentionally help Republican Donald Trump return to the White House.

Nixon, a 67-year-old lawyer, is stepping back into national politics for the first time since leaving office in 2017 and will serve as No Labels’ director of ballot integrity. He said in an interview that he was drawn to the role after learning that well-funded groups aligned with Democrats were working to stop No Labels from securing ballot access in key states.

He said that those seeking to block the group’s right to appear on the presidential ballot are attacking a pillar of American democracy.

“What do I say to those Democrats? I say, ‘You’re entitled to your opinion. But we are also entitled to use our constitutional and statutory rights to allow Americans to have another choice,’” Nixon told The Associated Press.

President Joe Biden and Trump have dominated the 2024 campaign conversation so far. But No Labels, a Washington-based group that promotes compromise, national unity, and centrist policy solutions, has been preparing for the strongest third-party presidential bid at least since Texas businessman Ross Perot earned nearly 19% of the popular vote in 1992.

Working with an operating budget of roughly $70 million, No Labels is taking steps to secure presidential ballot spots in roughly 20 states this year; the group has done so already in Alaska, Arizona, Arkansas, Colorado, Oregon, and Utah.

While No Labels has yet to nominate candidates for president and vice president, its leadership insists there is a path to victory for a centrist third-party ticket “if the two parties select unreasonably divisive presidential nominees.”

The group’s critics across the Democratic Party are terrified that No Labels will siphon votes that would otherwise go to Biden, who narrowly beat Trump in 2020 with a coalition that included moderate Democrats, independents, and disaffected Republicans.

No Labels’ leadership has promised a series of checks and balances that would allow the organization to withdraw its presidential ticket if it appears the group’s participation would help Trump win. No Labels has not outlined a detailed plan about that, and leaders acknowledge privately there is some urgency to come out with their specific safeguards, which would vary state by state. They intend to do so by “early fall.”

Anxious Democrats are unconvinced.

On Thursday, two prominent Democratic groups, the centrist Third Way and more progressive MoveOn, hosted private meetings on Capitol Hill with dozens of chiefs of staff and senior aides to House and Senate Democrats to emphasize the need to stop No Label’s presidential ambitions. In a nod to the seriousness of the Democratic establishment’s concerns, the meetings were held in both the House and Senate Democrats’ campaign headquarters.

“We told them what we have been saying consistently now for a long time: This is dangerous,” said Third Way co-founder Matt Bennett, who helped lead the briefing along with MoveOn’s executive director, Rahna Epting.

The organizers detailed data showing that a No Labels ticket would undercut Biden in the general election and warned that it could handicap vulnerable House and Senate candidates is tight elections. They also questioned that No Labels’ promise to withdraw its ticket if necessary to stop Trump.

No Labels’ leaders are furious.

“They are telling the elected leaders of this country right now that our ballot is a runaway train. And that is categorically false. That is propaganda. And that is why we’re bringing on a director of ballot integrity to stop it because it’s outrageous,” said No Labels’ founder Nancy Jacobson, a former Democratic fundraiser.

For now, Democrats are not willing to take Jacobson’s word for it.

“I don’t want to be doing this. I’d much rather focus on other things. I am concerned, genuinely,” Epting said. “They’re in over their head. They have not given any assurances that they’re clear and sober in their analysis. And when they talk about being able to put the horse back in the barn, they are not consistent about when or how they’re going to do that.”

“They’re just saying, ‘Trust us,’” Epting said. “We can’t. We don’t know you. And the stakes are too high.”

Meanwhile, Nixon joins a growing roster of former elected officials in both parties now affiliated with No Labels. Among the others: Sen. Joe Manchin, D-W.Va.; former Govs. Jon Huntsman Jr., R-Utah, Larry Hogan, R-Md., and Pat McCrory, R-N.C.; and former Connecticut Sen. Joe Lieberman, a Democrat who became an independent late in his political career.

Manchin and Huntsman, ambassador to China under President Barack Obama and to Russia under Trump, hosted a town hall in New Hampshire this month, driving speculation they may ultimately become the No Labels presidential ticket.

No Labels plans to hold a presidential nominating convention next April in Dallas, and the group is showing no signs of backing off its 2024 plans. With a massive budget fueled by anonymous donations, No Labels can afford to be patient in the fights ahead.

Democrats in Arizona filed a complaint this month with the secretary of state asking to have the group suspended until it discloses its donors. In May, Maine’s top elections official sent a cease-and-desist letter regarding No Labels voter registration efforts after claiming the group was misleading voters.

The group Citizens to Save Our Republic formed a super political action committee this month specifically designed to stop No Labels. The group’s members include Bennett from Third Way, several advisers to the anti-Trump Lincoln Project and former House Majority Leader Dick Gephardt, D-Mo.

Nixon, who declined to criticize Biden or Trump, said he understands that he is walking into a political firestorm. But he said he is passionate about No Labels’ constitutional right to secure a place on the ballot.

“I feel calm. I feel correct. I think we have a high moral ground here,” he said.

Republished with the permission of The Associated Press.