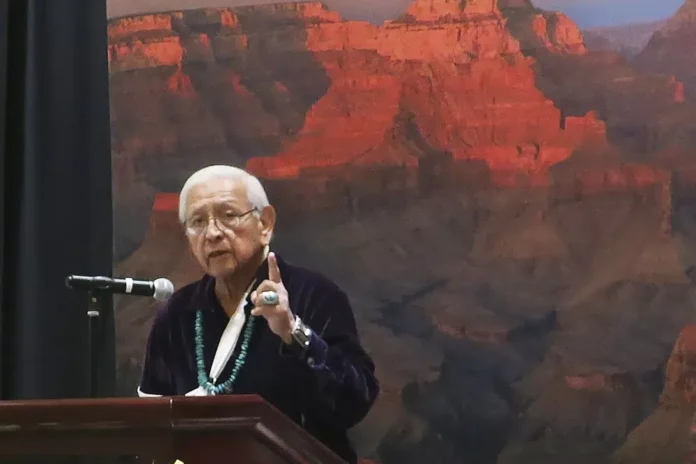

Peterson Zah, a monumental Navajo Nation leader who guided the tribe through a politically tumultuous era and worked tirelessly to correct wrongdoings against Native Americans, has died.

Zah died late Tuesday at a hospital in Fort Defiance, Arizona, after a lengthy illness, Navajo President Buu Nygren’s office said. He was 85.

Zah was the first president elected on the Navajo Nation — the largest tribal reservation in the U.S. — in 1990 after the government was restructured into three branches to prevent power from being concentrated in the chairman’s office. At the time, the tribe was reeling from a deadly riot incited by Zah’s political rival, former Chairman Peter MacDonald, a year earlier.

Zah vowed to rebuild the tribe, and to support family and education, speaking with people in ways that imparted mutual respect, said his longtime friend Eric Eberhard. Zah was as comfortable putting on dress clothes to represent Navajos in Washington, D.C., as he was driving his old pickup truck around the reservation and sitting on the ground, listening to people who were struggling, he said.

“People trusted him; they knew he was honest,” Eberhard said Tuesday.

Aspiring politicians on and off the Navajo Nation sought Zah’s advice and endorsement. He rode with Hillary Clinton in the Navajo Nation parade a month before Bill Clinton was elected president. Zah later campaigned for Hillary Clinton in her bid for the presidency.

He recorded countless campaign advertisements over the years in the Navajo language that aired on the radio, mostly siding with Democrats. But he made friends with Republicans, too, including the late Arizona U.S. Sen. John McCain, whom he endorsed in the 2000 presidential election as someone who could work across the aisle.

Zah was born in December 1937 in remote Low Mountain, a section of the reservation embroiled in a decades-long land dispute with the neighboring Hopi Tribe that resulted in the relocation of thousands of Navajos and hundreds of Hopis. He attended boarding school, graduating from the Phoenix Indian School, and rejected notions that he wasn’t suited for college, Eberhard said.

Zah attended community college, then Arizona State University on a basketball scholarship, where he earned a degree in education. He went on to teach carpentry on the reservation and other vocational skills. He later co-founded a federally funded legal advocacy organization that served Navajos, Hopis, and Apaches that still exists today.

Despite never having held a major elected position, Zah captured the tribal chairman’s post in 1982, campaigning in a white, battered 1950s International pickup that he fixed up himself, drove for decades, and which became a symbol of his low-key style, Eberhard said.

Under Zah’s leadership, the tribe established a now multi-billion-dollar Permanent Fund in 1985 after winning a court battle with Kerr McGee that found the tribe had the authority to tax companies that extract minerals from the 27,000 square-mile (69,000 square-kilometer) reservation. All coal, pipeline, oil, and gas leases were renegotiated, which increased payments to the tribe. A portion of that money is added annually to the Permanent Fund.

Former Hopi Chairman Ivan Sydney, whose tenure overlapped with Zah’s as chairman, said the two mended the acrimonious relationship between the neighboring tribes over the land dispute. They agreed to meet in person, without any lawyers, to come up with ways to help their people. Even after their terms ended, they attended tribal inaugurations and other events together.

Zah would say, “Let’s go turn some heads,” Sydney recalled Wednesday after visiting with Zah’s family. “We would go together, sit together, and get introduced together.”

Zah sometimes was referred to as the Native American Robert Kennedy because of his charisma, ideas, and ability to get things done, including lobbying federal officials to ensure Native Americans could use peyote as a religious sacrament, his longtime friend Charles Wilkinson said last year.

Zah also worked to ensure Native Americans were reflected in federal environmental laws like the Clean Water Act and the Clean Air Act.

Zah told The Associated Press in January 2022 that respecting people’s differences was key to maintaining a sense of beauty in life and improving the world for future generations. He struggled to name the thing he was most proud of after receiving a lifetime achievement award from a Flagstaff-based environmental group.

“It’s hard for me to prioritize in that order,” he said. “It’s something I enjoyed doing all my life. People have passion; we’re born with that, plus a purpose in life.”

Zah said he could not have done the work alone and credited team efforts that always included his wife, Rosalind. Throughout his life, he never claimed to be an extraordinary Navajo, just a Navajo with extraordinary experiences.

That resonated with students at Arizona State University, where Zah served as the Native American liaison to the school’s president for 15 years, boosting the number of Native students and the number of Native graduates. Zah also pushed colleges and universities to accept Navajo students — regardless of whether they graduated in the Arizona, New Mexico or Utah portion of the reservation — at in-state tuition rates.

“It’s thousands upon thousands of Native students not only from Navajo who he encouraged to stay in school, seek advanced degrees and was available to counsel when they hit the rough spots,” said Eberhard, who worked for Zah while he was chairman. “He completely altered the way Arizona State University works with Native students.”

Nygren said he first interacted with Zah as a student at ASU, struck by Zah’s speech, that he described as quiet and structured but powerful and vivid.

“To see him on the ASU campus brought a lot of inspiration to myself,” he said. “I probably wouldn’t have gone into construction management if he wasn’t so influential at ASU.”

Zah remained active in Navajo politics after he left ASU, as a consultant to other Navajo leaders on topics ranging from education, veterans, and housing.

“He was a good and honest man, a man with heart,” former Navajo President Joe Shirley Jr. said late Tuesday. “And his heart was with his family, with the people, with the youth and, certainly, with our nation, our culture, and our way of life.”

Republished with the permission of The Associated Press.