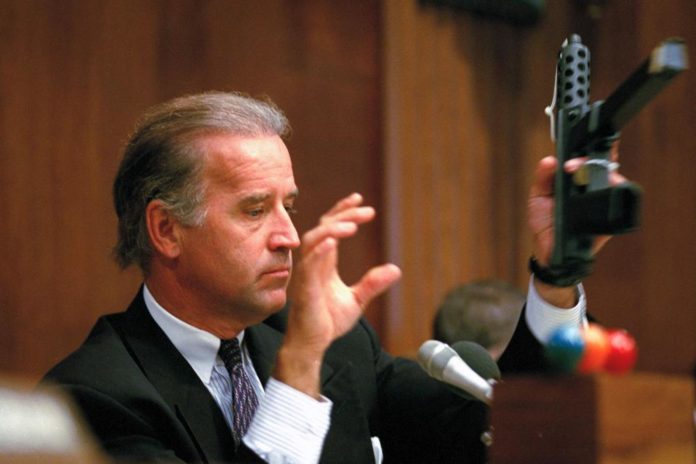

Joe Biden, then the chairman of the Senate Judiciary Committee, surveyed the collection of black, military-style rifles on display in the middle of the room as he denounced the sale of guns whose “only real function is to kill human beings at a ferocious pace.”

That was nearly three decades ago, and Congress was on the verge of passing an assault weapons ban. But the law eventually expired, and guns that were once illegal are now readily available, most recently used in the slaughter at an elementary school in Uvalde, Texas.

The tragedy, which came less than two weeks after another mass shooting at a grocery store in Buffalo, New York, has refocused Biden’s presidency on one of the greatest political challenges of his career — the long fight for gun control.

Over the years, Biden has been intimately involved in the movement’s most notable successes, such as the 1994 assault weapons ban, and its most troubling disappointments, including the failure to pass new legislation after the 2012 massacre at Sandy Hook Elementary School in Newtown, Connecticut. Now his White House, which was already trying to chip away at gun violence through executive orders, is organizing calls with activists and experts to plot a path forward.

“He understands the history of the issue. He understands how the politics have shifted,” said Christian Heyne, vice president of policy at Brady, the gun control advocacy organization. “He feels a sense of missed opportunities from the past, and he understands that this is his last chance to have an impact on gun violence in America.”

Even for a politician known for his passion, Biden’s reaction to the latest shooting in Texas has been searing.

“Where’s the backbone, where’s the courage to stand up to a very powerful lobby?“ Biden said Wednesday as he called for Congress to pass new laws.

Stef Feldman, a deputy assistant to the president, said the cascade of deaths — from Buffalo to Uvalde to everyday shootings that don’t generate nationwide headlines — only increases the urgency of the administration’s efforts.

“Every story that we hear about individuals lost to gun violence provides more energy, more of a drive to continue the work,” she said. “If we can save even one life by pushing a little harder on a creative policy idea, it’s worth it.”

But executive action — such as Biden’s order targeting ghost guns, which are privately made firearms without serial numbers — might be the best the White House can do if Republicans in the Senate remain opposed to new restrictions and Democrats are unwilling to circumvent filibusters.

More challenges could come in the courts, and even the ghost gun rules may become tied up in litigation.

“We’ve got to be clear,” said John Feinblatt, president of Everytown for Gun Safety. “This is the Senate’s job. It’s time for the Senate to actually step up and do something.”

The first new try fell far short on Thursday. A measure to take up a domestic terrorism bill, which could have opened debate touching on guns, drew just 47 of the 60 votes needed to break a filibuster.

It’s a far different situation than when Sen. Biden was working on gun legislation years ago. Fears about violent crime helped foster bipartisan compromises, and conservative rhetoric about gun ownership was less extreme.

First, Congress passed the Brady Handgun Violence Prevention Act in 1993, requiring a background check when someone buys a gun from a federally licensed dealer. The measure was named for James Brady, the White House press secretary who was shot and wounded when John Hinckley Jr. attempted to assassinate President Ronald Reagan in 1981.

Next, Congress approved the assault weapons ban as part of the Violent Crime Control and Law Enforcement Act in 1994. The law outlawed specific guns, such as the AR-15 and restricted the type of military-style enhancements that firearms could have.

However, the ban contained a sunset provision, and it was not renewed in 2004. Although the vast majority of shootings are committed with handguns, military-style semiautomatic rifles are staples of the country’s deadliest massacres.

One of these weapons was used at Sandy Hook, where 26 people, including 20 children, were killed.

The violence shocked the nation, and President Barack Obama asked Biden, then the vice president, to lead a new push for gun control. Sens. Joe Manchin, D-W.V., and Pat Toomey, R-Pa., crafted legislation that would have expanded background checks.

In a speech less than three months after the shooting, Biden said, “the excuse that it’s too politically risky to act is no longer acceptable.”

He recalled successfully pushing for the assault weapons ban years earlier even though the National Rifle Association warned that he was going to be “taking your shotgun away.”

“That kind of stuff doesn’t work anymore,” Biden added.

But it did work, and the legislation failed in the U.S. Senate. Biden described the vote as a betrayal of families who lost children at Sandy Hook, saying, “I don’t know how anybody who looked them in the eye could have voted the way they did today.”

Darrell A. H. Miller, a Duke University law professor who is an expert on the Second Amendment, said the political landscape had already changed.

“It’s fair to say that the issue of guns has become even more polarized,” he said. “And the intensity of gun rights opposition to any kind of gun regulation of any description has become more inflexible.”

Two years ago, guns became the leading cause of death among children and teenagers, outpacing car crashes. There are roughly 400 million guns in the country, more than one for every person. Military-style weapons are a staple of some Republican campaign advertisements.

“The reality is, we’re not keeping up with the pace of the gun lobby to arm citizens,” said Fred Guttenberg, whose daughter was killed at Marjory Stoneman Douglas High School in Parkland, Florida, in 2018.

“It’s time to start asking,” Guttenberg said, “why are Republicans so diametrically opposed to doing whatever it takes to save lives?”

There have been some successes at the state level, including a recent proliferation of so-called red flag laws, which allow authorities to take guns away from those deemed mentally unstable.

But Adam Winkler, a law professor at the University of California in Los Angeles, said those victories haven’t matched efforts to loosen restrictions. He noted that some states allow people to carry guns, even concealed, without permits.

“That’s something that was pretty much unheard of when Joe Biden joined the Senate,” he said.

When Biden launched his candidacy for the Democratic presidential nomination, he said he wanted to bring back the assault weapons ban “even stronger.”

“And this time,” he wrote in a New York Times op-ed in 2019, “we’re going to pair it with a buyback program to get as many assault weapons off our streets as possible as quickly as possible.”

But there has been no political path forward in the narrowly divided Senate, and Biden’s major initial legislative efforts have been focused on coronavirus relief and infrastructure.

A few months after taking office, the president bristled when a reporter asked if he was failing to prioritize gun control.

“I’ve never not prioritized this,” he said. “No one has worked harder to deal with the violence used by individuals using weapons than I have.”

On Wednesday, Biden sounded like a president who was preparing one more push to target gun violence.

“I spent my career, as chairman of the Judiciary Committee and as vice president, working for commonsense gun reforms,” he said.

“These actions we’ve taken before, they saved lives. And they can do it again.”

Republished with the permission of The Associated Press.