An incarcerated woman who testified at a trial Monday over the quality of health care in Arizona prisons tearfully recalled her frustration about the length of time it took to be diagnosed and treated for multiple sclerosis.

Kendall Johnson detailed her repeated attempts to get help for what started as numbness in her feet and legs in 2017 and was diagnosed as multiple sclerosis in 2020.

In a series of medical assistance requests made on her behalf, Johnson complained about inaction in her medical care and requested new doctors as the growing weakness in her legs caused her to regularly fall to the ground, leading in one instance to her suffering a broken foot.

The 37-year-old Johnson, who is in a wheelchair and has a speech problem that makes it difficult at times to understand her, said she can’t brush her teeth, must wear diapers, had to until recently pay fellow prisoners to feed her because of neglect from staff at the prison and typically spends her days laying in bed counting ceiling tiles.

“I have feeling in my legs and can move them now,” Johnson testified of her improvements since receiving effective medication.

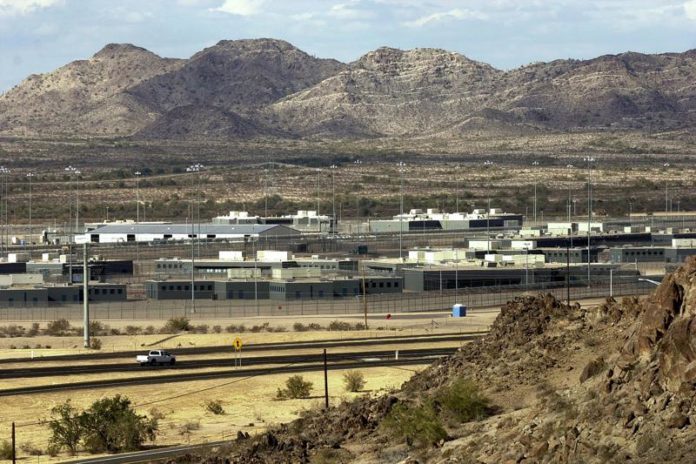

Johnson was the first witness at the trial over health care for more than 27,000 people incarcerated in Arizona’s state-run prisons. The trial was called after a judge threw out a 6-year-old settlement resolving the case, saying the state showed little interest in making many of the improvements it promised under the deal.

The judge had concluded $2.5 million in fines against the state for noncompliance with the settlement wasn’t motivating Arizona to comply, faulted the state for making erroneous excuses and baseless legal arguments, and said the failure to provide adequate care for prisoners led to suffering and preventable deaths.

Lawyers for the prisoners are asking the judge to take over health care operations in state-run prisons, appoint an official to run medical and mental health services there, ensure prisons have enough health care workers, and reduce the use of isolation cells, including banning their use for prisoners under age 18 or those with serious mental illnesses.

They said Arizona’s prison health care operations are understaffed and poorly supervised, routinely deny access to some necessary medications, fail to provide adequate pain management for end-stage cancer patients and others, and don’t meet the minimum standards for mental health care.

The Arizona Department of Corrections, Rehabilitation, and Reentry has denied allegations that it was providing inadequate care, delayed or issued outright denials of care, and failed to give necessary medications. Its lawyers said the prisoners can’t meet key elements in proving their case — that the state was deliberately indifferent to the risk of harm to prisoners and that the health care problems occur across the state-run prison system, not just a particular prison.

A court-appointed expert has previously concluded that understaffing, inadequate funding, and privatization of health care services are significant barriers in improving health care in Arizona’s prisons.

At first, Johnson said she told was told the numbness in her legs was neuropathy and given medications that didn’t work.

A doctor ordered an MRI for her in 2018 but didn’t provide a diagnosis. In a November 2019 request for help, she said she had been with a doctor for a year yet still didn’t know what was going on with her body.

She got an MRI in early 2020 and was able to get seen by another physician specializing in neurology, who concluded Johnson had MS and wanted two more MRIs. As she waited for an appointment, Johnson said she learned the doctor wasn’t accepting new patients because of the pandemic.

Under questioning from a lawyer representing the state, Johnson acknowledged she has access to medical providers on a regular basis and wasn’t told by a prison medical office that her neurologist was taking on new patients — she instead got that information from her grandmother, who called the doctor’s office.

Republished with the permission of the Associated Press.